When the trumpet sounded

everything was prepared on earth,

and Jehovah gave the world

to Coca-Cola Inc., Anaconda,

Ford Motors, and other corporations.

The United Fruit Company

reserved for itself the most juicy

piece, the central coast of my world,

the delicate waist of America.

Pablo Neruda, “The United Fruit Co”

Although I don’t like giving lectures on history and usually just try to write down my thoughts, this article had been on my mind for a long time, and every time I ate a banana, my urge to write grew stronger. Most of you must have seen labels on bananas: for some reason, those labels always had the words “Dole” or “Chiquita” on them. They still do. But what are these magic words (that have seemed mysterious to me since I was a child)? Dozens and perhaps hundreds of books have been written about these them, many studies have been conducted. In this article I will try to sum up this knowledge to shed some light on these labels with which bananas are “branded” all over the world. I have no intention of explaining the health benefits of bananas—that is a matter for nature and science, and there is no issue there. The controversy is only about the labels and brands created by us humans. Go on, peel a banana and start reading…

Contrary to popular belief, bananas are not native to the Western Hemisphere. Its original habitat is South or Southeast Asia. Banana spread mainly by human migration—for example, the Polynesians took it to the Hawaiian Islands—or by conquest—it came to the West with the expansion of the Arab world. The biological term for banana, “musa”, is an Arabic word, which is actually a derivative of a Sanskrit word, reflecting the fact that the Arabs first encountered bananas in India (James Wiley, The Banana: Empires, Trade Wars, and Globalization, p. 3). This fruit grows in certain countries, but the companies that sell it around the world are from completely different countries. One of them is a country that has next to no production of this fruit. Yes, this country is the United States. Banana cultivation in the United States is very limited, and in 2009 it accounted for only 0.001% of worldwide banana production. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the world’s major banana producers between 2000 and 2008 were India, Ecuador, Brazil, China and the Philippines.

However, the companies that supply different parts of the world with this fruit are owned by the United States. The most famous US company engaged in fruit imperialism was founded in 1899 and was originally called the United Fruit Company. There is a term sometimes used in politics, “banana republic”. It was coined by the American writer O. Henry in his satirical novel Cabbages and Kings, but it was the United Fruit Company that was instrumental in the creation of the banana republic phenomenon. A banana republic is a country with an economy squarely dependent on banana exports. In the modern and narrow sense, it refers to the Central American countries, whose economy and political life were strongly influenced by the United Fruit Company (later United Brands and now Chiquita). This influence mainly took the form of military intervention and coups. The establishment of this company is considered the foundation of the “Banana Empire”. The historical need for such a company has to do with the properties of bananas. Banana is a perishable fruit. It has a very short shelf life after it ripens. Thus, timing is very important in the banana industry. Harvest them while they are still green, transport them to a port, load them onto a ship, carry them to markets, complete the ripening process, and transfer them to wholesaler and local retailers.

The period between harvest and consumption is four to five weeks, during which bananas travel 1,500 miles by land and about 2,000 to 6,000 miles by water to reach their markets, where their shelf life is no more than 5 days. Therefore, the geography of banana production and consumption is determined by banana’s need for higher levels of efficient organization. This can take a variety of forms, but one thing is certain: it is virtually impossible for independent farmers to act on their own to make sure that bananas are delivered to markets on time. In his book, James Wiley says that Ellis identifies the banana industry’s first stage as the period from 1870 until 1898, during which independent farmers in Central America sold fruit to private North American shipping firms (James Wiley, The Banana: Empires, Trade Wars, and Globalization, p.5). This was not yet the commercial form of the banana industry. Before switching to it, Central American governments became interested in creating more effective transportation networks to link inland population centers to the Pacific and Caribbean coasts. They invited specialists from North America and the United Kingdom to build the railroads. All this led to the key event in the history of the banana industry in the Western Hemisphere: the 1884 signing of the landmark Soto-Keith contract between Costa Rican President Bernardo Soto and US businessman Minor Keith.

In short, the contract obligated the Americans to build a railroad connecting the port of Puerto Limón with the capital, San José. In fact, the main motivation in building the Costa Rican railroad was to transport coffee, not bananas, to European markets, because the main share of exports in the country’s economy was coffee. Before that, coffee had had to travel a longer route along the Pacific port of Puntarenas, and a railroad would significantly reduce that journey. The first part of the project had been financed by British capital, leading to a massive national debt. Keith renegotiated that debt, which Costa Rica would guarantee with export revenues. In return, the American businessman was given 800,000 acres of land, amounting to 7 percent of the country’s territory. Keith was obligated to develop this land. He realized later that he needed to generate capital to continue the construction of the railroad, so he began to grow bananas on the land given to him, effectively laying the foundation for Costa Rica’s banana industry. However, once the construction was completed, the situation changed and the railroad now served the rapidly growing banana business. In 1892 and 1894, Keith signed additional contracts with the Costa Rican government to build a network of railroads linking the expanding banana zones in the country with the port. Thus, the National Railway Company was founded in 1900.

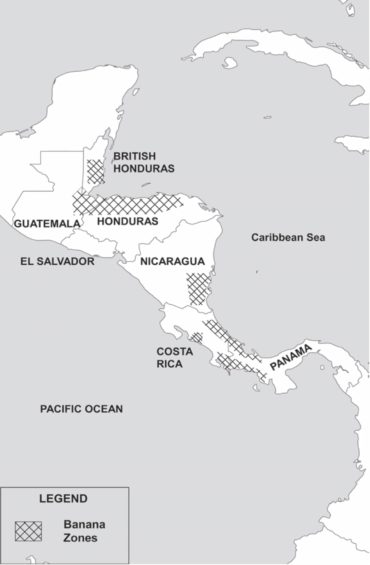

The same policy was pursued in other countries: building railroads to link banana zones and ports, thus playing the role of midwife to the nascent Banana Empire. In Guatemala, the construction of the Northern Railway began in the 1980s to connect the main coffee plantations and the Pacific port of Puerto Barrios. In Honduras and Colombia, railroad construction was also used to acquire land and expand the banana business, turning many Central American countries into banana republics in the truest sense of the term.

Honduras, where bananas account for over 60 percent of overall national export, where the influence of banana companies on the economy has been growing since the early 20th century, is considered the first “banana republic” in Latin America (Timothy E. Josling, Timothy G. Taylor, Banana Wars: The Anatomy of a Trade Dispute, p. 98). The beginning of the commercial banana industry dates back to 1899, with the granting of the first banana concession in Honduras, which led to the establishment of the predecessor to the United Fruit Company. The United Fruit Company was formed through the merger of Minor Keith’s Boston Fruit Company and the Tropical Trading & Transport Co. Throughout history, their main competitor has been the Standard Fruit Company (now the Dole Food Company). The United Fruit Company was the dominant economic power in Guatemala from 1906 to 1972 and influenced the country’s politics. Since its incorporation in 1899, the company had owned or leased approximately 3.5 million acres of land in Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Panama, Cuba, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Colombia and Ecuador (Timothy E. Josling, Timothy G. Taylor, Banana Wars: The Anatomy of a Trade Dispute, p. 99). Keith also added his Panama-based Snyder Banana Company to the “empire”. One month after the merger, the company bought 7 commercial companies in Panama and Honduras, then the Colombian Land Company, which owned banana production in Santa Marta (Charles D. Kepner, Social Aspects of the Banana Industry).

After that, interesting events began to unfold. Keith’s Northern Railway Company monopolized Costa Rica’s rail transport after leasing the operation of the country’s national railroads, using it to gain dominance in Costa Rica’s banana industry. United Fruit Company either owned or leased on favorable terms the International Railways of Central America in Guatemala, Tela and Trujillo Railroads in Honduras, Caribbean coast Changuinola Railroad in Panama, Magdalena National Railway in Colombia, Chiriqui National Railway in Panama Pacific and National Railroad of Honduras. Only a few lines, mostly in Honduras, were owned by rival companies (James Wiley, The Banana: Empires, Trade Wars, and Globalization, p. 14).

After that, interesting events began to unfold. Keith’s Northern Railway Company monopolized Costa Rica’s rail transport after leasing the operation of the country’s national railroads, using it to gain dominance in Costa Rica’s banana industry. United Fruit Company either owned or leased on favorable terms the International Railways of Central America in Guatemala, Tela and Trujillo Railroads in Honduras, Caribbean coast Changuinola Railroad in Panama, Magdalena National Railway in Colombia, Chiriqui National Railway in Panama Pacific and National Railroad of Honduras. Only a few lines, mostly in Honduras, were owned by rival companies (James Wiley, The Banana: Empires, Trade Wars, and Globalization, p. 14).

James Wiley points out that rail transport remained a key tool in the company’s land acquisition policy. In addition to Costa Rica and Guatemala, the company’s subsidiaries acquired more than 175,000 acres of land in Honduras. However, this land was not granted in contiguous blocks. It was dividing into alternating areas, with intervening areas controlled by the government. This was done to prevent total domination by a foreign company within a given region (Charles D. Kepner, Jay H. Soothill, The Banana Empire: A Case Study of Economic Imperialism).

Now having full control of the railroads in Costa Rica, the company used various methods against its competitors. The most important of these was making sure that rivals’ products were damaged by altering train schedules. They also entered into exclusive long-term contracts to purchase fruit with independent farmers. The company’s oceangoing ships were known as the Great White Fleet. By 1930, the company had 100 ships, which essentially constituted the navy of the Banana Empire. The ships had refrigerated cargo holds to carry bananas as well as other goods and could even carry passengers. The company normally did not trust other companies to ship its bananas, most likely expecting to be treated in the same way it treated its competitors (James Wiley, The Banana: Empires, Trade Wars, and Globalization, pp. 20-21).

In 1970, the new owner of the company changed its name to United Brands. Since 1984, the company has been known under its now familiar name, Chiquita Brands International, as if its bloody past had been erased.

Some authors say that the company’s influence in Latin America led to the creation of “black legends” about it, such as interference in national politics and labor abuse. But history is in plain sight… In the next section, I will look back at the two most famous of these interventions.

Banana politics…

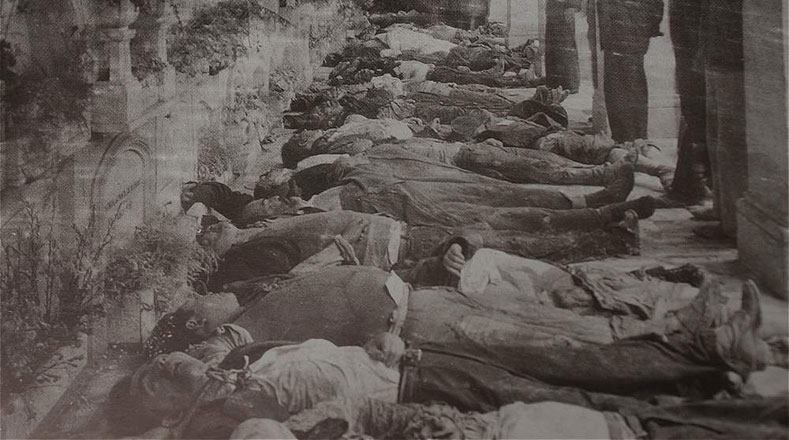

The name of this company is mentioned in almost all the books I have found on the Internet, which discuss, in varying degree of detail, the pressure exerted by the US on Latin American countries. Even works of fiction hint at the massacres committed by this company. Although the poem “The United Fruit Co” by Pablo Neruda quoted in the epigraph of this article clearly states its purpose, Miguel Angel Asturias’s The Green Pope and Gabriel García Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude are less explicit about it. Marquez describes in his novel the events of 1928 in his native Colombia, known as the Banana Massacre. In the general chronology, this was perhaps the first in the list of the atrocities committed by the United Fruit Company. In his book Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World, Dan Koeppel notes that in 1927, Colombia’s political system tended to lean against the banana conglomerate. The national assembly ordered an investigation into the United Fruit Company’s land acquisition policies. The ruling conservative party’s grip on power was loosening. The biggest labor action ever faced by a banana company began on October 30, 1928, when 32,000 workers went on strike. Their main demands were medical treatment, proper toilet facilities, payments in cash. They asked to be considered true employees rather than subcontractors and thus afforded labor protection, as little as it meant with weak Colombian labor laws (Dan Koeppel, Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World, p. 87). The company panicked. The government sent troops to occupy Magdalena. The proof that the company was directly affiliated with the United States is the December 5, 1928 telegram from US Ambassador to Colombia Jefferson Caffery to US Secretary of State Frank Billings Kellogg. It said, “I have been following the … strike through United Fruit Company representative here; also through minister of Foreign Affairs who on Saturday told me government would send additional troops and would arrest all strike leaders and transport them to prison at Cartagena; that government would give adequate protection to American interests involved.”

What followed is a known real historical fact, but it would be more effective to add some artistic flavor to the dryness of history. Here is what Marquez says about it, using the genre of magical realism to depict the events.

“It had been signed by General Carlos Cortes Vargas and his secretary, Major Enrique García Isaza, and in three articles of eighty words he declared the strikers to be a “bunch of hoodlums” and he authorized the army to shoot to kill.

After the decree was read, in the midst of a deafening hoot of protest, a captain took the place of the lieutenant on the roof of the station and with the horn he signaled that he wanted to speak. The crowd was quiet again.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” the captain said in a low voice that was slow and a little tired. “You have five minutes to withdraw.”

The redoubled hooting and shouting drowned out the bugle call that announced the start of the count. No one moved.

“Five minutes have passed,” the captain said in the same tone. “One more minute and we’ll open fire.” (Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude).

Although the exact number of people killed in the incident is unknown, Marquez puts it at around 3,000.

One of the most notorious incidents involving United Fruit is the US military coup in Guatemala. Guatemala’s dictator Ubico was overthrown in 1944 and Juan José Arévalo came to power. As soon as Arévalo became president, he introduced a new comprehensive education program and a new labor code to protect the rights of rural and city workers. Trade unions sprang up. This weakened the United Fruit Company, the owner of vast lands, who was exempt from taxes and inspections, and held railroads and ports in its hands. Arévalo said in his farewell speech in 1951 that he had had to deal with 32 conspiracies financed by the company. His successor, Jacobo Arbenz, extended the reforms. New roads and the port of San José broke the company’s monopoly on fruit transportation. Besides, United Fruit was using only 8 percent of its land, which extended from ocean to ocean (Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America, p. 152). Although these reforms were aimed at steering the country away from feudalism and creating a capitalist agricultural economy, they led to an international smear campaign against the country. Mark Zepezauer writes in his book The CIA’s Greatest Hits that US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles convinced Eisenhower that Arbenz must be overthrown, thus landing a $20 million job for Allen Dulles’s CIA. The CIA launched a propaganda offensive and hired 300 mercenaries to sabotage railroads and gas stations (Mark Zepezauer, The CIA’s Greatest Hits, p. 37). Col. Castillo Armas, trained in Kansas, was also sent by the United States to invade his own country, with air support from F-47 bombers. Testifying before a Senate Subcommittee” on July 27, 1961, the US ambassador to Honduras said that the “liberating” operation in 1954 had been worked out by a team that included himself and the US ambassadors to Guatemala, Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Galeano writes that Allen Dulles, the number one man at the CIA at the time, cabled them his congratulations on their accomplishment. Dulles had previously been on the United Fruit’s board of directors, and a year after the invasion his seat was occupied by another CIA man (Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America, p. 113).

Aze.Media

References:

1) James Wiley, The Banana: Empires, Trade Wars, and Globalization

2) Timothy E. Josling, Timothy. G. Taylor, Banana Wars: The Anatomy of a Trade Dispute

3) Charles D. Kepner, Social Aspects of the Banana Industry

4) Charles D. Kepner, Jay H. Soothill, The Banana Empire: A Case Study of Economic Imperialism

5) Dan Koeppel, Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World

6) Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

7) Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America

8) Mark Zepezauer, The CIA’s Greatest Hits