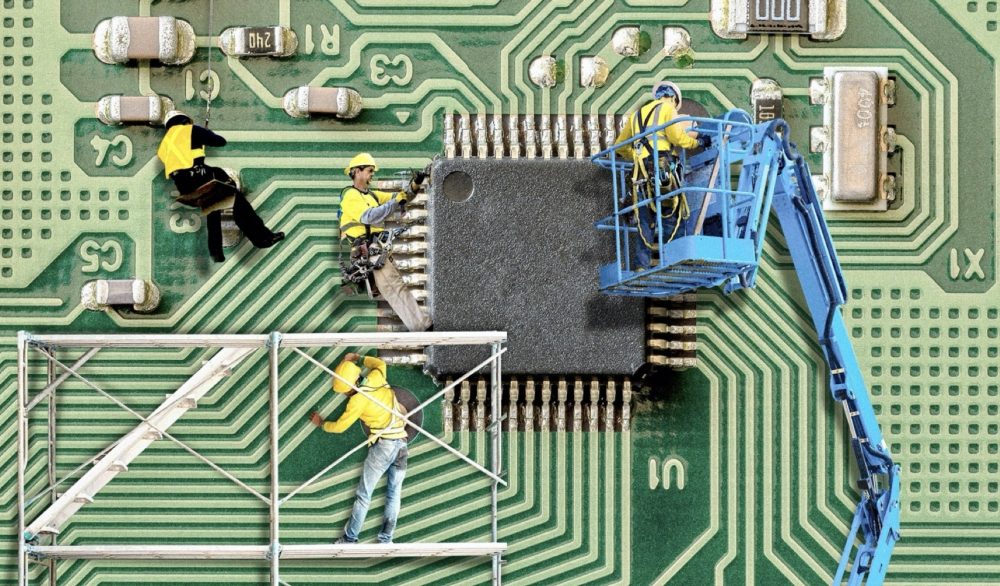

It would not be an exaggeration to say that our world is now built on microchips. The chip, this backbone of many engineering applications within the colossal, now robotized, industry, from automobiles to home appliances, mobile phones, computers, game consoles, spacecraft, satellite and missile technology, will pave the way for the fourth industrial revolution.

The annual production of semiconductor chips—the power source of every electric device we see around us—is close to 1 trillion, which means 128 chips for every person in the world. The shrinking consumer market and disruptions in the global supply chain in the first months of the pandemic reduced the demand for chips. However, East Asian countries easing domestic quarantine regulations in the following months, in particular, economic activity in China surging again, on the one hand, and the transition to remote work and learning to prevent the spread of infection in many countries on the other, increased demand for electronic devices such as computers, smartphones, game consoles, etc., which in turn led to a revival of the global chip market and, eventually, to an immense shortage. $439 billion worth of semiconductor chips were sold last year—a 6.5% growth compared to the same period in 2019.

The first victim of the crisis was the engineering industry. The shortage of chip supply forced the major corporations in the automotive industry, such as VW, Nissan, Mercedes, Honda, Volvo and Ford, to slow down or stop production completely. There are serious ongoing problems with the production of electronic and navigation systems of modern cars, which are highly dependent on chips, as well as with the manufacture of electric motors for hybrid and electric vehicles.

According to the estimates by IHS Markit, a British-based financial information and analysis provider, the chip shortage will result in 700,000 fewer vehicles produced in the first quarter of 2021. According to Morgan Stanley analysts, this figure will grow to 1.5 million units during the year, costing the global automotive industry more than $60 billion in material damage. US-based General Motors (GM) alone will reportedly lose about $2 billion in revenue this year due to the chip shortage.

Intel (USA), Samsung (South Korea) and TSMC (Taiwan), the world’s three leading microchip suppliers, are working tirelessly at full capacity to cope with the crisis. There are three types of companies engaged in the production of semiconductor chips: companies like Intel, Samsung, Micron (USA), STMicroelectronics (France-Italy-Netherlands) and Toshiba (Japan) do everything from the design of chips from scratch to the manufacturing process, at their own facilities. Corporations such as Qualcomm (USA), Nvidia (USA), HiSilicon (China), Apple (USA), Mediatek (Taiwan), Microsoft (USA) and Google (USA) only design and market chips (fabless company), outsourcing the manufacturing to save money and time to companies like TSMC (Taiwan), SMIC (China), GlobalFoundries (USA) and UMC (Taiwan), who deal only with this part of the process.

Note that the Taiwanese TSMC is the only manufacturer of microchips for all types of Apple smartphones, tablets and computers in the world. TSMC is also the largest supplier of such giants as Qualcomm, Nvidia and HiSilicon and the manufacturer of chips designed by Xilinx (USA), one of the suppliers of electronic components for the fifth-generation fighter aircraft F-35 of the US Air Force. In short, 60% of chips belonging to US companies are made by TSMC.

TSMC, one of Taiwan’s largest companies, is the world leader in chip production. The current market value of TMSC is $573 billion (for comparison, the current market value of a giant like Samsung is $567 billion), which makes it one of the top 10 largest companies by market capitalization. Overloaded with production orders, TSMC works around the clock to build new fabrication facilities.

Taiwan being at the epicenter of the global technology race, its chip production rose by 20% last year, reaching $107.5 billion, which accounts for 15% of Taiwan’s economy.

The production of semiconductor chips consisting of billions of microscopic transistors is a business few countries can cope with. Only two companies in the world, Samsung and TSMC, manufacture 5 nm and 7 nm microchips used in high-end smartphones. Only the Dutch-based ASLM can provide the equipment that allows manufacturing chips of these sizes. Samsung and TSMC, who are currently working on the production of 3 nm microchips, are two and four years ahead of their biggest competitors in the industry—the US Intel and the Chinese SMIC, respectively. TSMC spent $19.5 billion in 2020 to build a facility intended to manufacture exclusively 3 nm microchips.

Most of the chips mentioned so far would be impossible to make without the technology and licensing of the British ARM. Qualcomm, Samsung, Apple, Nvidia and other world’s leading chip manufacturers create new designs under its license, tailoring the ARM core designs to their needs. Basically, the production of high-performance microchips for smartphones and tablets is possible within the standards provided by ARM: in other words, 90% of the world’s smartphones are equipped with microprocessors based on ARM technology. Chips for computers are made on the basis of Intel’s X86-64 instruction sets.

By the way, in September last year, it was announced that Nvidia would buy Arm for $40 billion, giving the United States a monopoly in this area.

With the introduction of the next-generation 5G technology and artificial intelligence-based devices, there is a growing need for super-powerful chips. Currently, the most powerful and smallest microchip used in the global chip market is the TSMC-manufactured 5 nm chip, and it is mainly installed in high-end devices.

For example, Apple’s latest generation 5 nm A14 bionic chip, used in the iPhone 12 series and fourth-generation iPad tablets, has 11.8 billion transistors, while Huawei put 15.3 billion transistors in the 5 nm Kirin 9000 chip used in its Mate series P40 smartphones.

As we know, production of semiconductor chips is made possible by technological cooperation of several countries, which naturally creates interdependence between those countries. The manufacturing of a high-tech chip requires the design provided by the ordering company, the license by the British ARM, the fabrication by the Taiwanese TSMC and the equipment by the Dutch ASML (in particular, extreme ultraviolet lithography technology vital for processing 5 and 7 nm microchips).

The delays in this chain supply caused by the onset of the pandemic, as well as the complex geopolitical situation in East Asia, the center of microelectronics—Taiwan’s disputed status, its geographical proximity to China and Beijing’s view of the island as an integral part of it are the factors that induce the elimination of the dependency of the US chip industry on TSMC. The US companies have 47% of the global chip sales market, but the US fabrication share is only 12%. Having outsourced 90% of chip fabrication to foreign companies, the United States experienced economic difficulties due to the chip shortage in domestic engineering industry, especially during the pandemic, necessitating the new administration and Congress to take practical actions.

On February 24 this year, US President Biden signed an executive order to stimulate the manufacturing of strategically important technological products by domestic resources and strengthen the supply chain to cope with the chip shortage problem.

The US Congress, which is to prepare a $37 billion package to support domestic chip production, had previously persuaded TMSC to invest $12 billion in new facilities in Arizona. Alongside with commercial chips, the TSMC facilities in Arizona will produce microchips for the US military industry. In addition, Intel last month announced a budget of $20 billion for the construction of new fabrication facilities.

On the far East front, SMIC, China’s largest chipmaker, said in March it would allocate $2.5 billion to stimulate domestic production. The Shanghai-based SMIC is also the world’s fifth largest semiconductor manufacturer, and in December last year, the Trump administration imposed restrictions on the export of high-tech products to SMIC by the United States and its allies.

Although most of the world’s electronic equipment is manufactured in China, these devices require chips and technology imported from the United States and its allies. According to former US President Trump, Chinese-based technology companies are a major threat to the national security of the United States, so large-scale sanctions have been imposed on high-tech corporations such as Huawei, ZTE, SMIC and others to prevent Chinese companies from accessing American technology. The ban prohibits US companies, as well as any equipment operating on US software, from selling any technology, as well as any equipment operating on US software, to or manufacturing any components for Huawei without special permission. In March, the US administration put diplomatic pressure on the Dutch company ASML and stopped it from selling its products to SMIC. The alleged links between the sanctioned companies and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA), as well as allegations of cybercrime and espionage, gave Washington an opportunity to make this move. As some of the equipment used by TSMC in the fabrication process is of US origin, it was forced to refuse to fulfill orders from Chinese companies. Following that, Huawei’s HiSilicon stopped production of its Kirin microchips in September last year, failing to withstand the sanctions. HiSilicon was TSMC’s second-largest customer after Apple, and the Kirin microchip series designed for Huawei smartphones had performance characteristics to compete with Qualcomm’s Snapdragon microchips.

Being pressured in the international arena and still suffering from sanctions, China has given a special focus to the development of innovative technologies, mainly the chip industry, in its next (14th) five-year economic planning project, which began in March this year. Complete independence in the field of chip supply and the establishment of a sustainable supply chain are part of the Chinese government’s fundamental plans. China currently has the capacity to manufacture only 16% of the chips it needs, and the government aims to increase that figure to 70% by 2025.

The main goal of the official Beijing, which invests billions of dollars every year in the development of this industry, is to minimize its technological dependence in the chip industry dominated by the United States and its allies and to prevent possible future sanctions.

The 20th century struggle for natural resources, especially world oil reserves, has given way to the struggle for control of the chip industry in the 21st century.

It is undeniable that the microchip, one of the most complex and expensive components in the world, affects everything from the speed of the devices we use daily to international political and economic relations. Gaining a place in the core of national security, said integrated circuit will continue to be one of the main objects of struggle in the ongoing US-China high-tech rivalry for the title of the superpower in the coming years.

As consumer electronic devices become “smarter”, they have an increasingly complex structure. The rapid introduction of 5G wireless networks in various industries, artificial intelligence infiltrating almost every aspect of our lives, the demand for microchips growing at an exponential rate—all this increases the likelihood of the crisis in the semiconductor industry persisting until the end of this year.

Aze.Media