But the application and development of applied and exact sciences alone cannot solve one of the main problems of humankind—the correct and fair use of the fruits of these sciences.

The social sciences are trying to solve this problem, taking on the function of managing applied and exact sciences in order to maximize and optimize the benefits they offer. Applied and exact sciences create opportunities, and social sciences make sure that these opportunities are used in the best possible way. But, if we look back at the entire history of mankind, it is safe say that the social sciences do not withstand the burden of the achievements of applied sciences. Something seems to be missing in the social sciences, some factor is always disregarded or cannot be taken into account due to the impossibility of foreseeing the future, and plans for a higher goal, such as a just society, fail.

However, it is possible to imagine a society in which applied, exact and social sciences are brought together with pinpoint accuracy and complement each other as a kind of perfect mechanism. One can dream, as they say, and this is what many writers and philosophers have done throughout history. Depicting such ideal societies in their works, they, perhaps unknowingly, created such literary genre as utopia. Over time, another kind of works appeared, depicting the abyss between the exact and social sciences. The new genre was called dystopia, or cacotopia, or, to give a clearer idea of its essence, anti-utopia.

Dystopia is the opposite of utopia, and literally means “bad place.” Works of this genre depict an unwanted social order—for example, a society with highly developed applied sciences, in which technical discoveries and inventions are used for unimaginable evil purposes. In contrast, utopian works depict a desirable society, in which scientific discoveries are used only in the best way possible. Hence the difference in how easily these genres are perceived by the reader. Utopia is the things and way of life people dream of and believe to be perfect. Therefore, utopian works are easier to understand. After all, any brilliant innovation the reader encounters on the pages of a utopian novel might have at some point come to the reader’s mind as well, as a dream, a fantasy. A utopian work is, in a way, a chronicle of human dreams. You can read Thomas More’s Utopia or Campanella’s The City of the Sun in one breath.

The inhabitants of the city of Amaurot in Utopia do not attach false values to gold and silver and consider it unfair to deprive another person of something that person needs if it is of no use to them. Such way of thinking is easy for us to understand, and throughout the book we constantly encounter examples of similar behavior that we consider perfect. Utopia reminds us of the things buried deep in our hearts, forgotten under the influence of the existing unjust system, the things we are afraid to talk about. It as if reflects the catechisms of a religion of perfection rebelling against a hypocritical system that seeks to make people forget who they really are.

But understanding and perceiving the genre of dystopia is much more difficult. Sometimes this difficulty can stem simply from the style of the literary work. The “mathematical” writing style used in Zamyatin’s novel We can create certain difficulties for the reader, but it is due to the writing itself. The main challenge comes from something else, and this is typical of almost all dystopias: they depict things that we can hardly imagine, things we have never thought of in our life. It is not easy for the reader to immediately understand what is happening in We, or to imagine Integral, the fire-spitting spaceship created to subjugate other civilizations, because this is far from what the reader has dreamed of all their life.

Could the gap between the applied and social sciences be so wide that the purpose of a spacecraft, a product of technology, is to conquer other civilizations? However, if we think about the political landscape of our world, the idea will no longer seem so strange. But we still cannot imagine a house with transparent glass walls, with the curtains that can be drawn only to have sex after getting a special pink ticket. It sounds wild and incredible, something that the social sciences cannot cope with. This is an undesirable society, and the undesirable is unpredictable and endless. These things are difficult for the reader to perceive, because there are no makings of such malice in the reader’s heart.

Could the gap between the applied and social sciences be so wide that the purpose of a spacecraft, a product of technology, is to conquer other civilizations? However, if we think about the political landscape of our world, the idea will no longer seem so strange. But we still cannot imagine a house with transparent glass walls, with the curtains that can be drawn only to have sex after getting a special pink ticket. It sounds wild and incredible, something that the social sciences cannot cope with. This is an undesirable society, and the undesirable is unpredictable and endless. These things are difficult for the reader to perceive, because there are no makings of such malice in the reader’s heart.

In this sense, dystopia is much broader than utopia. For most people, perfection is quite concrete: bread, freedom, prosperity, justice. And utopia gives that to the reader. But the opposite is not a list of specific items. The opposite is injustice, and injustice can take millions of shapes. Yes, human justice by nature lags behind human injustice, outright losing when it comes to varieties. It is as if only a few out of millions of steps represent justice, and you walk and walk, and keep walking… Every place is dystopia and it is unpredictable.

Feminist dystopia and Hitler’s triumph

Another very interesting subgenre of science fiction is alternate history, in which alternate versions of real historical events are described in fantastical form. The first works of this genre date back to the 15th century. In the alternate history described in the novel The White Tyrant by the Valencian writer Joanot Martorell, the Ottomans failed to capture Constantinople.

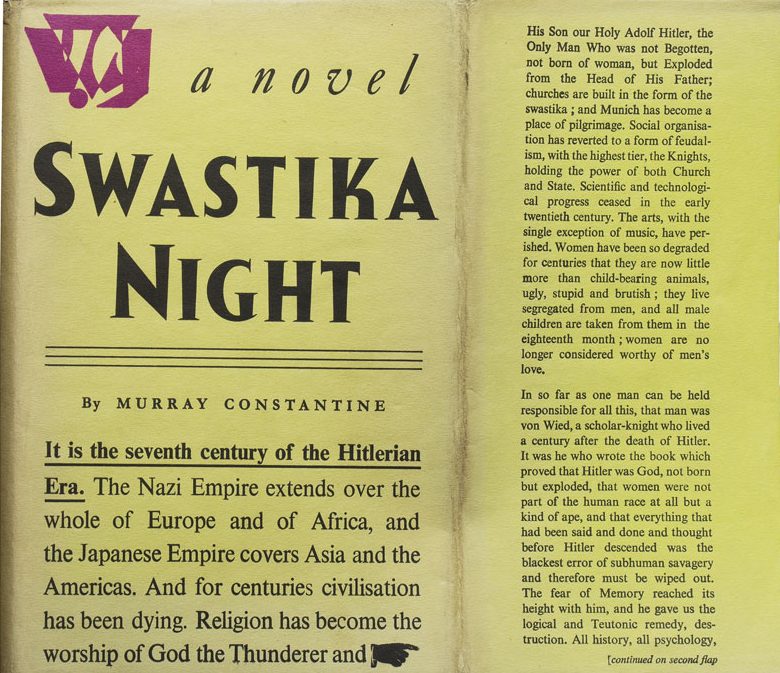

But the most interesting novels in the genre of alternate history were written in the 20th century. In these works, along with a description of an alternate course of events, the authors fantasize about the possible future in the alternate worlds. One of the most famous examples is Swastika Night by the English writer Katharine Burdekin, one of the masters of feminist dystopia. The plot of this 1937 dystopian novel gives every reason to categorize it as alternate history as well.

The novel is set in 2633. The Axis powers win after twenty years of war and gain control over the entire world. Hitler is declared a deity, and men worship him in special temples. Yes, only men, because women became the next target of the Nazis after the Jews. They call women soulless animals, and the concept of beauty is associated exclusively with the male sex. Therefore, women in this society are subjected to all kinds of oppression. From this point of view, the novel can also be called a feminist dystopia.

A society opposite to that described in Swastika Night can be found in another book, although it is not alternate history. Herland, a novel by one of the main representatives of the genre of feminist utopia Charlotte Perkins Gilman, is about a land inhabited only by women, where social justice reigns and there is no letter “M” in the alphabet. Although the short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” is considered the author’s best work, Herland is one of the most famous examples of feminist utopia.

This novel has certain shortcomings, mainly scientifically dubious elements. For example, the author describes women reproducing via parthenogenesis with no need for men. This is a direct reference to women’s reproductive rights and is supported by modern feminists. But the scientific feasibility of this method of reproduction is still debatable.

World War II and its results occupy the central place in the alternate history novels of the 20th century, and here we cannot but mention Philip K. Dick’s novel The Man in the High Castle. It too depicts the victory of the Nazis and their allies, with the United States being divided among the winners, and so on.

Dystopia in Azerbaijan

I would like to conclude this article with a couple of paragraphs about the dystopia genre in our country. I had my doubts as to whether I should, but then I watched Idiocracy and my mind was made.

The film begins with two people, a US soldier and a prostitute, being put in hibernation as part of a suspended animation experiment, to be unfrozen in a year. But the officer conducting this experiment is arrested, the laboratory is closed, a café opens in its place, and everyone forgets about the test subjects.

When the two finally wake up and get out of their containers, 500 years have passed, during which evolution turned backwards. The world became a huge dump. People have become stupid, with their IQ level abysmally low. Wheat is watered with energy drinks, and there is nothing but pornography on TV. The audience in the movie theater laughs, watching Ass, a film that won many awards, including an Oscar: an hour and a half of a naked farting ass on the screen. It may sound too harsh, but I am going to say it anyway: what our TV audience watches and laughs at today is not much different from that Ass.

Our country can be easily compared to any dystopian scenario. But Idiocracy reminds Azerbaijan not only in the failure of the social sciences in this society, but also in the very low level of development of exact and applied sciences. More precisely, there is no scientific development. But there are two scenes from Idiocracy that I associate with Azerbaijan the most: when the police arrest one of the main characters, and when the court appoints his punishment. All the scenes of the film caused me some fear and excitement, and some scenes were painful to watch, but the scenes with the police and the court were much easier for me to bear. They reminded me too much of the reality in which we live, so they seemed quite ordinary. This dystopia is already here. Except perhaps our officials look more serious in their suits and ties and do not drink beer at work.

Aze.Media

If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at [email protected]